The challenge of urban freight.

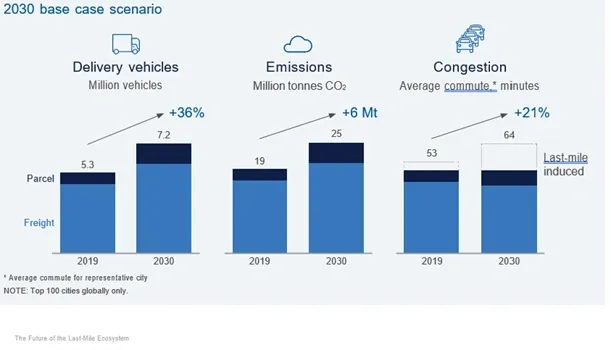

The World Economic Forum estimates emissions from delivery traffic will increase by 32% and congestion by over 21% in the top 100 cities globally through 2030.

In London, there are an estimated 9,400 premature deaths per annum from long-term exposure to PM2.5 and NO2. Freight vehicles account for 29% of PM2.5 in London (Source: London Councils.gov).

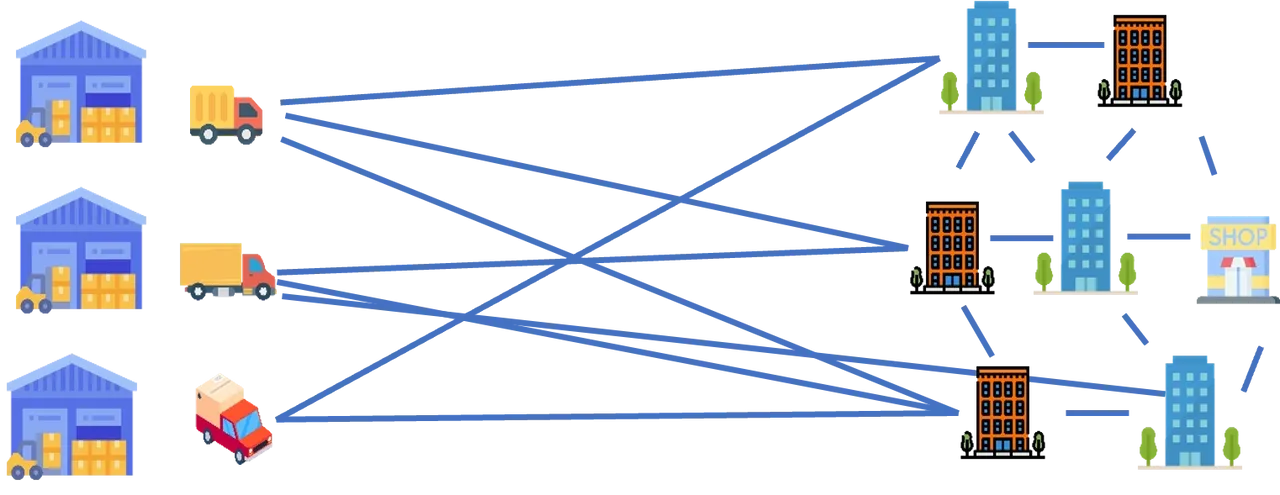

Retailers and B2B suppliers have built competing supply chains responding to eCommerce growth and customer demand for rapid deliveries. This is evidenced by the significant increase in vans in London with 3.7bn van miles (Light Commercial Vehicles) in 2019. In the UK there were 4.1m licensed vans in 2019 up 93% since 1994 and this trend is set to continue.

Just-in-time delivery (JIT), which emerged in the 1970s from the Japanese ‘Kaizen’ concept (the Japanese word for continuous improvement), has been fundamental to the evolution of ‘lean’ supply chains and reductions in stock levels. However, whilst reducing waste and inventory, JIT has over time, increased freight vehicle movements through ‘little and often’ deliveries

These macro trends have increased supply chain complexity, and this ripples through to the so-called final mile, increasing freight vehicle movements and the resultant pollution and congestion.

Current policy interventions including congestion charging, Ultra-Low Emission Zones (ULEZ) and the shift to electric vehicles are making an impact. However further interventions are needed to meet the environmental, health, and quality of life challenges caused by increasing freight vehicle numbers in cities.

The case for consolidation centres.

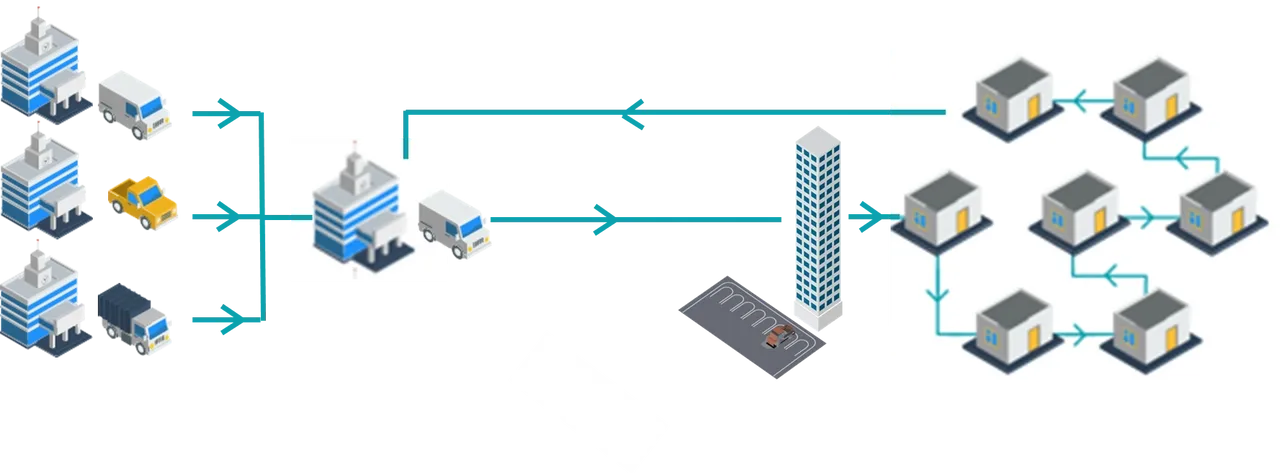

Construction consolidation centres, logistics operations where construction materials are consolidated before onward shipment to an urban construction site, have been successfully used for many years. Consolidation centres are also used in airport logistics where there is a limited and controlled access route with mandated security or duty-free protocols for deliveries air side. Those with longer memories will recall the move away from direct-to-store deliveries for supermarkets to centralised distribution (in other words consolidation) in the 1980s and 90s. In all these cases, there is a ’captive’ supply chain with a clear commercial and/or compliance imperative.

Freight consolidation helps reduce urban vehicle movements locally however there are currently real and perceived barriers to wider adoption including the additional costs, increased lead times, and the ‘exporting’ of emissions and congestion to another part of the city or surrounding area.

As a result, B2B urban freight consolidation centres for non-construction goods, everything from milk to furniture, have not seen the take-up that was hoped for by authorities and councils. City of London set a precedent when they approved planning for the now completed 22 Bishopsgate by including the obligation to consolidate freight deliveries. This was written into the Section 106 planning obligations placed on the developers, and they had to find a solution to meet these legal obligations. City of London has now applied the same approach to other new offices in the city cluster currently under planning and construction and other cities are watching these initiatives closely.

Currently, there are only a handful of UK providers offering specialist operational capabilities with access to appropriate site facilities, but the bigger challenge is commercial.

Current barriers to adoption.

Whilst legally requiring a developer to only receive consolidated deliveries (and collections) helps reduce pollution and congestion locally, the commercial and operational practicalities of meeting this obligation are a challenge. Currently, there are only a handful of UK providers offering specialist operational capabilities with access to appropriate site facilities, but the bigger challenge is commercial. These are two sides of the same coin – no commercially attractive scale market, no investment in facilities and operations. So, who pays?

The answer currently is the businesses, shops, cafes, and restaurants based in the buildings paying the service charge. The requirement for consolidation can materially increase the service charge level at the building when compared to neighbouring already-built properties with no requirement for consolidation. Moving to consolidation for an existing building adds costs to the established service charge and in the current economic climate, businesses are increasing their already laser focus on rent and service charges.

Consolidation of deliveries to streets and districts also faces similar commercial challenges to adoption. Neighbouring retail businesses, for example, that are part of large organisations will often have a centralised procurement and distribution set up which can be a barrier to consolidation.

Tackling climate change, air pollution and congestion are the priorities of our time, and freight consolidation is one of the interventions businesses can make, but near-term commercial barriers are dampening take up and Section 106 legislation whilst forcing change, currently only really addresses new developments in cities.

Reducing complexity – ‘virtual consolidation’.

At CurbCargo our mission is to reduce pollution and congestion from freight vehicles in cities. Our research has identified several barriers to achieving this mission:

- Data – there is a lack of granular freight movement data to make informed decisions / build value cases for physical consolidation etc.

- Insights – the environmental impacts of deliveries and collections are not widely evaluated or quantified (e.g., Scope 3 emissions under the GHG protocols).

- Holistic approach – physical consolidation can reduce vehicle movements in one local area but can ‘export’ the movements to another area i.e., physical consolidation centres do not reduce upstream supply chain complexity in of themselves.

- Single point solutions – Current consolidation centres are in general addressing a single or small cluster of end-user requirements i.e., there could be a proliferation of urban consolidation centres adding to complexity rather than reducing vehicle movements.

- Costs – there is potentially a significant on-cost to operate consolidation centres.

- Collaboration – between neighbouring businesses on ESG initiatives is often limited and periodic.

In response, we have developed the CurbCargo platform to:

- Manage – manage delivery/collection bookings into buildings, campuses, and districts to build the freight vehicle movement data bottom up.

- Understand the impact & gain insights – estimate the impact of these deliveries on the environment and health using our methodology developed in partnership with Imperial Consulting (Imperial College).

- Prompt interventions to make a difference – use the data and insights to prompt changes in how businesses order goods, for example, reduce the delivery frequency, ask suppliers to change the type of vehicle and;

- Foster collaboration– suggest collaboration with neighbouring businesses on carrier/supplier initiatives such as combining deliveries, joint ordering and in some cases moving to common suppliers. This creates a community of like-minded businesses and acts as a catalyst for wider ESG collaboration.

‘Virtual consolidation’ can help reduce vehicle movements ahead of, alongside, or instead of physical consolidation. Historic barriers to collaboration are breaking down as climate change and public health concerns reshape consumer and business behaviour, and Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) policies are rightly in the spotlight for investors and employees.